Corrections officer in Clallam County kept job for decades, despite violations

A corrections officer, who sexually assaulted inmates in a small jail on the Olympic peninsula, kept his state prison job for years despite a slew of violations.

Editor's Note: This story contains depictions of sexual assault.

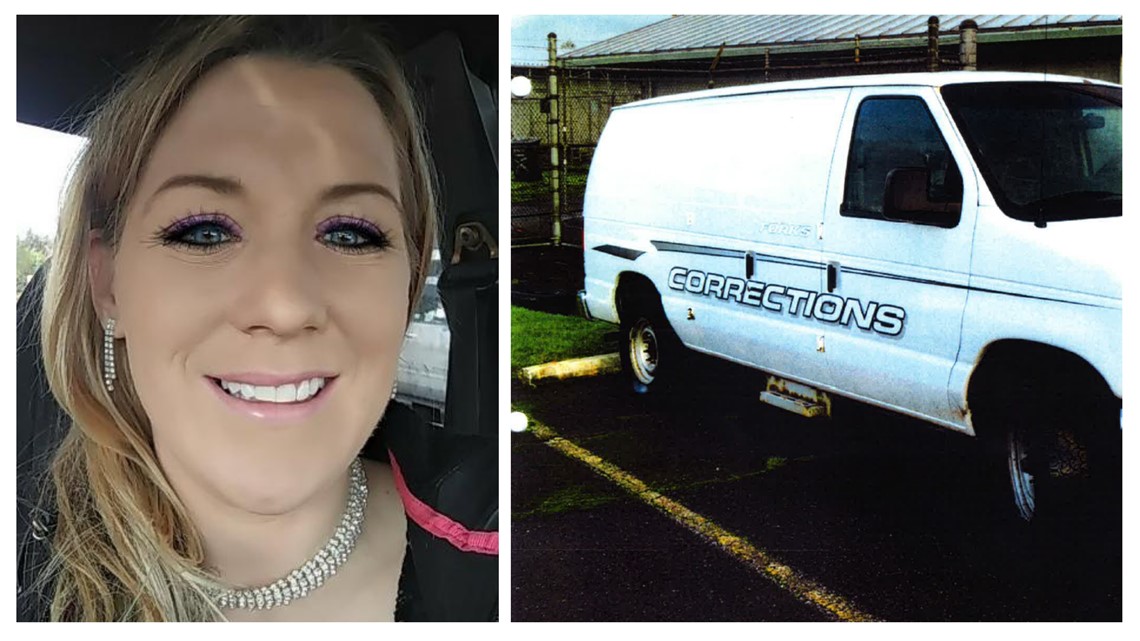

CLALLAM BAY, Wash. — Morgan Lee was sexually assaulted by the man who was paid to protect her.

And even though she said she never wanted to see her abuser – a Forks jail guard – again, she tuned in to his virtual sentencing hearing early last year to watch as a Clallam County judge sentenced him to spend 20 months behind bars.

“He looked defeated and powerless, which is exactly how I felt,” said Lee, 38, of Shelton. “I wanted him to know that it was not right what he did to me and to anybody else.”

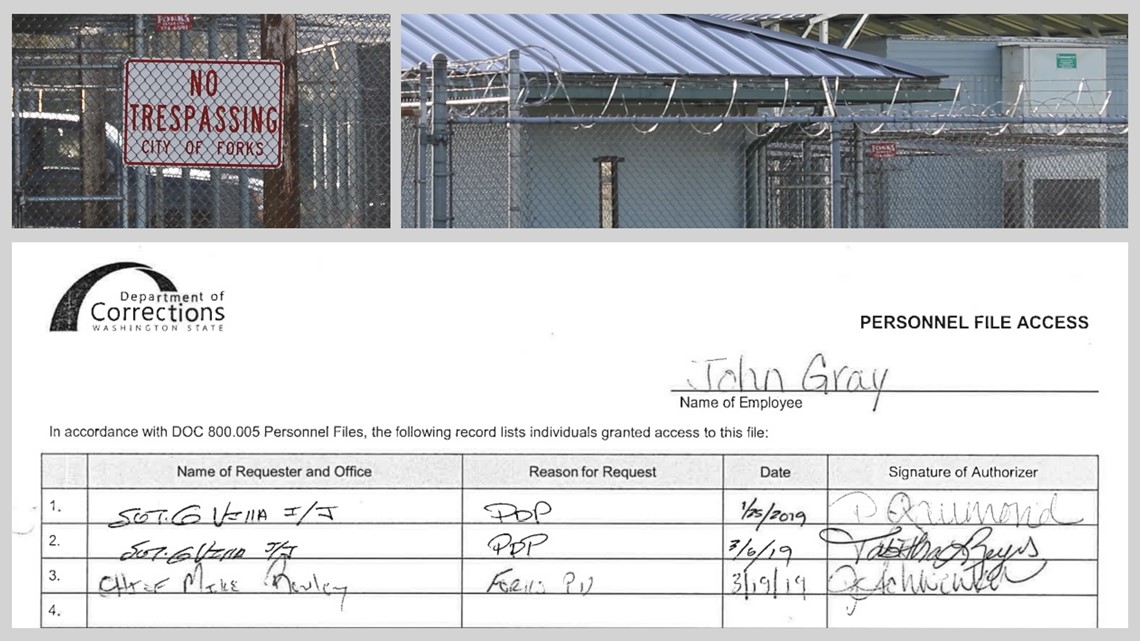

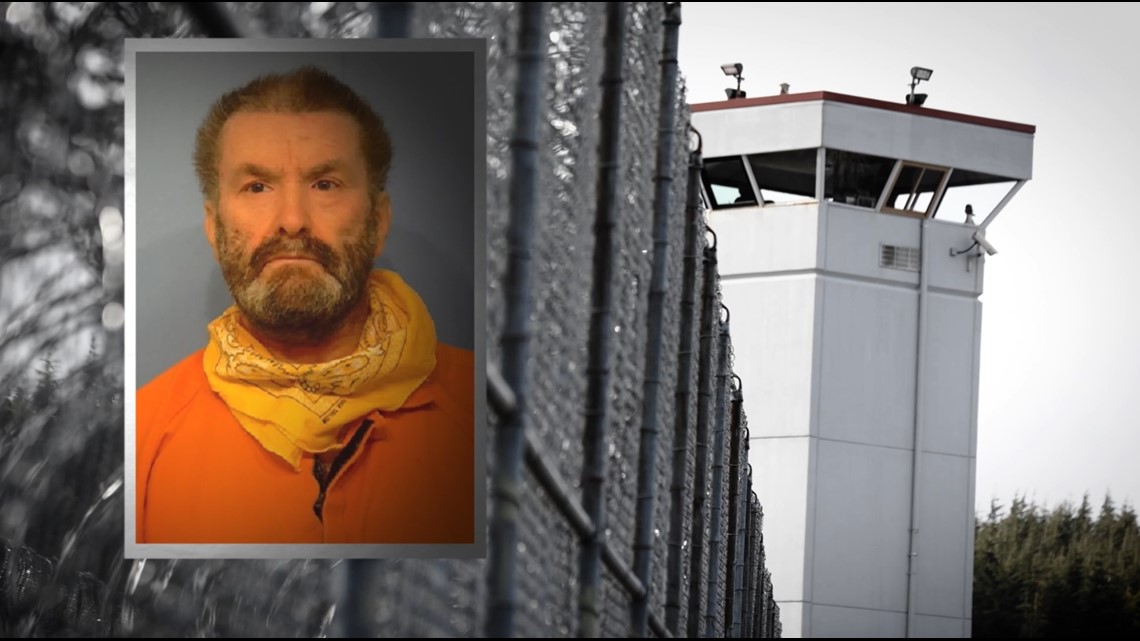

John Russell Gray, the corrections officer who pleaded guilty to sexually assaulting Lee and three other women while they were inmates at the Forks Correctional Facility in 2019, had a thick disciplinary record and at least two dozen complaints against him over his 24-year career as a corrections officer.

Yet, officials at nearly every level — from the city of Forks to the state Department of Corrections (DOC) and Gray’s local corrections union — repeatedly made decisions that allowed the predator to remain on the job as a guard, with power over a vulnerable population, a three-month KING 5 investigation found.

Reporters scoured thousands of pages of disciplinary records, city and state documents, law enforcement records, and internal emails between Gray’s union representative and prison staff. The documents were obtained from public disclosure requests or provided to KING 5 by an attorney representing the family of a fifth alleged victim in a federal lawsuit against the city of Forks.

Before Gray’s short stint as a Forks jail guard in 2019, he worked for more than two decades as a corrections officer at the Clallam Bay Corrections Center, an adult male prison located about 30 miles north of the city of Forks. As a guard there, he faced repeated discipline – from letters of reprimand to suspensions – for misconduct that included racism toward coworkers, vulgarity toward offenders, security breaches and sexual harassment. Gray, 53, was fired from his prison job at one point only to later be reinstated, according to DOC records.

“He acted like he was bulletproof – like nothing he said or did would get him in trouble,” said Kimberly Seward, Gray’s former co-worker. “And he was pretty much right.”

The officer’s misconduct in his prison job shouldn’t have been a secret to the Forks leaders who offered him work at the small city jail. Gray consented to a complete background check after applying for the Forks job. Forks Police Chief Mike Rowley personally reviewed Gray’s DOC file four weeks before he hired him, according to a record of the people who accessed Gray’s prison file.

And even after the city of Forks fired Gray eight months into his job at the jail, his career as a corrections officer wasn’t over. Within five months, the state brought him back on as a full-time guard at the Clallam Bay prison and – state records note – he got a raise.

The DOC, the city of Forks and an attorney for John Gray declined KING 5’s requests for interviews. No one from the city of Forks responded to questions.

A DOC spokesperson said the agency followed its protocol throughout the course of Gray’s prison employment, and prison officials were not immediately clued in to his misconduct in Forks.

A pattern of complaints

Kimberly Seward, a former corrections officer at the Clallam Bay Corrections Center, said she used to call in to work sick just to avoid spending time around Gray.

“I physically couldn't get out of bed because I knew this person was there – that Gray was going to be there. The thought of that was exhausting and hopeless,” said Seward, who worked with the guard for five years between 2013 and 2018. “It was extremely uncomfortable. I’d say, toxic.”

State records show Seward repeatedly voiced her concerns about the officer to prison bosses. In written complaints, she reported Gray “harassed” her and subjected her to a “hostile work environment” by yelling and consistently making bigoted, sexual and homophobic comments while on the job.

And she wasn’t the only staff member who spoke up. Between 2014 and 2018, at least seven other Clallam Bay Corrections Center employees filed written complaints about Gray’s behavior at work, according to a review of his DOC file.

“I do not feel safe working with Gray, and I worry for the unit staff,” one female corrections officer wrote in an email to her supervisor. “I feel something bad is going to happen."

Offenders at the male prison complained, too – including at least five prisoners who reported Gray for sexual misconduct. In April 2015, a transgender man filed a complaint alleging that Gray not only sexually harassed him but targeted other inmates as well.

“I’m afraid that the local here is trying to cover up sexual misconduct of (Corrections Officer) John Gray, who tends to sexually harass and make sexual comments towards inmates and has been doing that quite a bit,” the man told prison officials, before eventually requesting that DOC officials separate him from the guard.

DOC officials investigated the sexual misconduct complaints from all five offenders and closed them without action, noting in disciplinary records that they couldn’t prove the prisoners’ claims.

But some complaints from Gray’s coworkers would eventually lead to disciplinary action.

Discipline escalates

In January 2017, after Seward and two other employees filed complaints, Gray received a written letter of reprimand for “inappropriate, disrespectful and racially slanderous” comments about a Native American co-worker and an Asian supervisor.

“I was hoping that any sort of positive change that could happen would happen,” Seward said. “But unfortunately, that was not the case.”

A year and a half later in July 2018, the DOC suspended Gray for 15 days without pay for a string of other policy violations. Prison officials said he showed “inappropriate, disrespectful and unprofessional” behavior toward offenders and staff, shoved an inmate during an improper search and violated security protocol when he left two prison gates unlocked at once.

“He couldn’t do the basic necessities to treat people with dignity,” Seward said. “At that point, why are you keeping a problem employee?”

Three months after Gray’s suspension, the Clallam Bay prison superintendent concluded he was “no longer qualified” to serve as a DOC corrections officer, according to a disciplinary letter in his prison personnel file. Her comments came after prison investigators said Gray made “sexually-oriented comments and sounds” at a mandatory workplace training session intended to stop prison sexual misconduct.

Disciplinary records note Gray interrupted the class during a lesson, where two females demonstrated on video how to use sensitive techniques when searching transgender prisoners. Class instructors were “shocked” and “visibly upset” by Gray’s conduct, and state records show that a female administrative assistant who attended the February 2018 training told investigators she felt “trapped.”

As a result of the incident, the DOC fired Gray for sexual harassment in October 2018.

But his termination wouldn’t last long.

Rescinded discipline and one 'last chance'

Gray’s union, Teamsters Local 117, filed multiple grievances on his behalf – appealing his 2018 unpaid suspension and his termination for sexual harassment, according to Gray's disciplinary records.

As a union member, Gray’s case would typically be reviewed by a neutral arbitrator with authority to make a legally-binding and final decision.

But “to avoid the uncertainty of the outcome of arbitration,” a DOC spokesperson said the state chose to resolve the union disputes by negotiating a settlement agreement with Teamsters Local 117.

Under the “last chance” agreement, signed the month after the state fired Gray, prison leaders agreed to rescind his termination and give Gray his job back. The DOC also committed to wiping from his file the 2017 reprimand for racism that originated with complaints from Seward and two other employees.

“After doing what was right and speaking up to stop these kind of things and having it ignored – having it disappear basically…you lose hope of having a healthy, decent work environment,” Seward said.

The last chance settlement agreement was scheduled to remain in effect for two years. It required Gray to complete a 15-day suspension before returning to his prison job. It also required him to refrain from engaging in future misconduct.

“The parties agreed that upon proof of any further inappropriate conduct by Gray towards others, DOC would terminate Gray, without the level of discipline being challenged by Gray or the union,” Tobby Hatley, a DOC spokesperson, wrote in a statement.

A new chance in Forks

Before he returned to his job at the Clallam Bay Corrections Center in late 2018, Gray applied for another job as a corrections officer at the Forks Correctional Facility.

City records show the small jail was in need of an “emergency hire” because of staffing shortages.

“We are currently down two positions,” Forks Police Chief Mike Rowley wrote in a memo to Forks Mayor Tim Fletcher in October 2018. “With the possibility of an injury putting staff in a grave overtime situation or danger, I would like to expedite the process of hiring.”

Prior to hiring Gray as a jail guard at $19.38 an hour in April 2019, the city of Forks conducted a background check, a polygraph examination and a psychological examination, according to Gray’s final offer of employment letter from the city.

During the background check process in March 2018, Rowley reviewed Gray’s DOC personnel file, according to a DOC record containing a list of the people who accessed the guard’s information.

Gray’s personnel file, reviewed by KING 5, includes details of his extensive history on the job – with records dating back to the late 90s when he first became a state employee. It contains Gray’s training records, letters of commendation and union grievances, in addition to copies of numerous complaints, prison investigations and disciplinary measures taken against him.

“It’s inconceivable that a leader could be looking at a record like this and say, ‘That’s the guy for my taxpayers. That’s the guy who I want to place with other men and women who serve and for me to expose to the citizens of Forks,’” said Sarah Prescott, a Michigan-based civil rights and employment law attorney who specializes in cases involving prison misconduct. “It’s just terrifying and appalling.”

It’s not clear if the city of Forks reviewed the complete personnel file or if city officials were aware that Gray had been terminated for sexual harassment when he applied for the job.

Rowley and Forks City Attorney-Planner Rod Fleck did not respond to questions about Gray’s employment, the city’s hiring process or its policies pertaining to sexual misconduct.

Megan Coluccio, a Seattle-based attorney representing the city and some of its leaders in a federal lawsuit related to John Gray’s misconduct, also did not respond to questions.

“The City does not comment on pending litigation,” Coluccio wrote in an e-mail.

'I was at the mercy of him'

After getting a new job as a Forks jail guard in the spring of 2019, Gray resigned from his full-time job at the Clallam Bay prison.

Instead, he stayed on as an on-call prison guard, where he continued to work “sporadic and intermittent” shifts, according to a DOC spokesperson.

During his eight months of employment at the Forks jail, law enforcement and court records show Gray went on to sexually assault Morgan Lee and three other female inmates.

“It’s humiliating. It’s violating. It’s damaging. It hurts,” Lee said of her former jail guard’s actions. "In just a few seconds, he took a lot from me.”

Lee met Gray on her ride to jail in September 2019. He was the one tasked with transporting her on an hours-long drive from Mason County to the Forks Correctional Facility. She was sentenced to do time in the jail because she failed to complete court-mandated community service following a misdemeanor.

During the transport, as Lee's hands and legs were in shackles, Gray reached under her skirt while they were stopped at a gas station, and he groped her, according to law enforcement records and her own account of Gray’s actions.

“He forced this on me. He did this with me completely helpless, in shackles,” she said. “I was at the mercy of him – powerless to do anything, and I think that’s how he preferred it”

Gray’s sex crimes involving the other three women happened while they were locked up inside the Forks jail between the summer and fall of 2019. According to law enforcement records, Gray provided bail money to two of the women after he sexually assaulted them.

The details of the incidents that led to Gray’s criminal case wouldn’t become public until months after his city employment ended.

But Gray’s unusual behavior during the night shift caught the attention of a coworker during his first few months on the job. The coworker, a Forks police officer, reported he saw the guard where he didn’t belong – in the hallway with a female inmate, who “looked very uncomfortable” and had a “deer in the headlights look” when she was spotted with the jail guard, according to law enforcement records.

Gray’s supervisor at the time, Sgt. Ed Klahn, documented the incident in an August 2019 observation report about the guard's work performance. But Klahn admitted later to a Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office deputy who investigated Gray’s criminal case that he let the incident slide.

“I did just kind of sweep it under the carpet because I thought he was such a hard worker,” Klahn said to the deputy in a recorded interview. “I just thought he just put himself in a bad situation trying to get the job done, so I counseled.”

In November 2019 – eight months into Gray’s employment as a Forks jail guard, a fifth woman tearfully reported to police officers that she was a victim of sexual harassment. The inmate, Kimberly Bender, told officers that Gray stalked her in her cell at night – whispering lewd and sexual comments while she was incarcerated over the course of several months.

Investigators who interviewed Bender believed her story and cited multiple reasons for why they thought she was “telling the truth.” But at the conclusion of a swift internal review, Rowley said they were “unable to substantiate” her allegations, even as they fired the jail guard during the investigation.

Forks leaders cited Gray's probationary employment as a reason for the termination.

Bender ended up taking her own life. Gray ended up taking his old job back.

Backed by the union

Hundreds of internal emails between Gray, his union representative and DOC officials show Teamsters Local 117 consistently protected him throughout the course of his career as a correctional officer, including after he was fired from the city of Forks.

Following his termination, Gray asked the Clallam Bay prison superintendent to bring him back on as a full-time guard. His union representative successfully convinced prison officials to extend the terms of his “last chance” agreement and give Gray another shot.

“Unions have a lot of opportunity to affect either justice or injustice in these scenarios, and they carry a lot of weight,” said Prescott, the civil rights attorney. “But I think a lot of this has to go to the people who could have stopped it – who could have said, ‘Enough, we’re not doing this.’”

When Gray took his old job back in April 2020, he returned to the prison with a clean slate. An email exchange between Gray’s union representative and a DOC employee shows prison management agreed to allow Gray to “start fresh” with no mention in performance evaluations of his previous prison discipline.

He also received a raise of nearly $300 a month, according to a state record of his salary. DOC officials said his salary increase was part of a standard raise that all corrections officers received under the terms of their 2019 collective bargaining agreement.

Hatley, the DOC spokesperson, said there was “no basis” for prison officials to conduct a background check when they offered Gray another full-time job at Clallam Bay because the corrections officer “never left DOC employment” when he went to work at the Forks jail.

“DOC was not informed of any unprofessional or inappropriate behaviors towards individuals in the custody of the City of Forks when Gray requested to return to work a regular, full-time schedule at DOC,” Hatley wrote

Paul Zilly, a Teamsters Local 117 spokesperson, also explained union officials weren’t clued in to what happened in Forks.

“When Gray returned to full-time employment at the DOC after working at the Forks jail, we had no knowledge of the deplorable acts he was engaged in while he was employed there,” Zilly wrote in a statement.

Teamsters Local 117 declined an interview request and did not respond to questions about the union's representation of Gray.

Convicted for his crimes

In May 2020, the month after Gray returned to the Clallam Bay prison, his crimes in Forks caught up with him.

Sheriff deputies arrested him at work, and he was later charged and convicted of the sex crimes that forever changed the lives of his victims.

The DOC terminated Gray a final time in January 2021, about a month after he pleaded guilty to two felony and two misdemeanor counts of custodial sexual misconduct.

Then, in February 2021, a Clallam County court judge sentenced Gray to return to prison, not as a guard but as a prisoner.

If you need help

If you have experienced sexual assault and need support, help is available.

King County Sexual Assault Resource Center’s 24-hour Resource Line - 888.99.VOICE