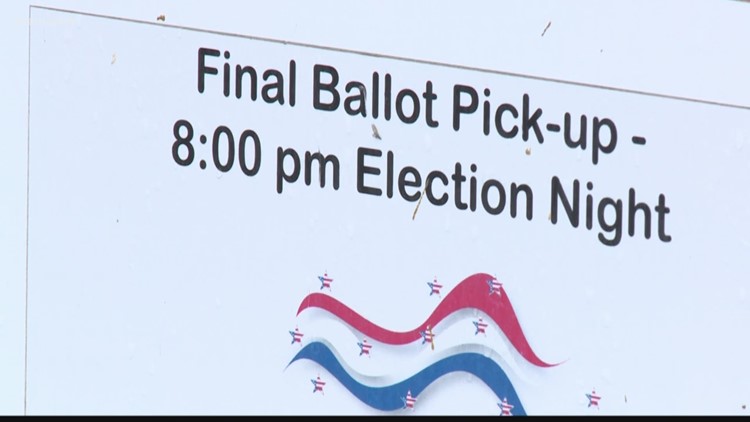

PULLMAN, Wash. — There have been a lot of questions surrounding voting by mail as many voters are using it for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Americans are breaking early voting records. Millions have already cast their ballots ahead of the presidential election.

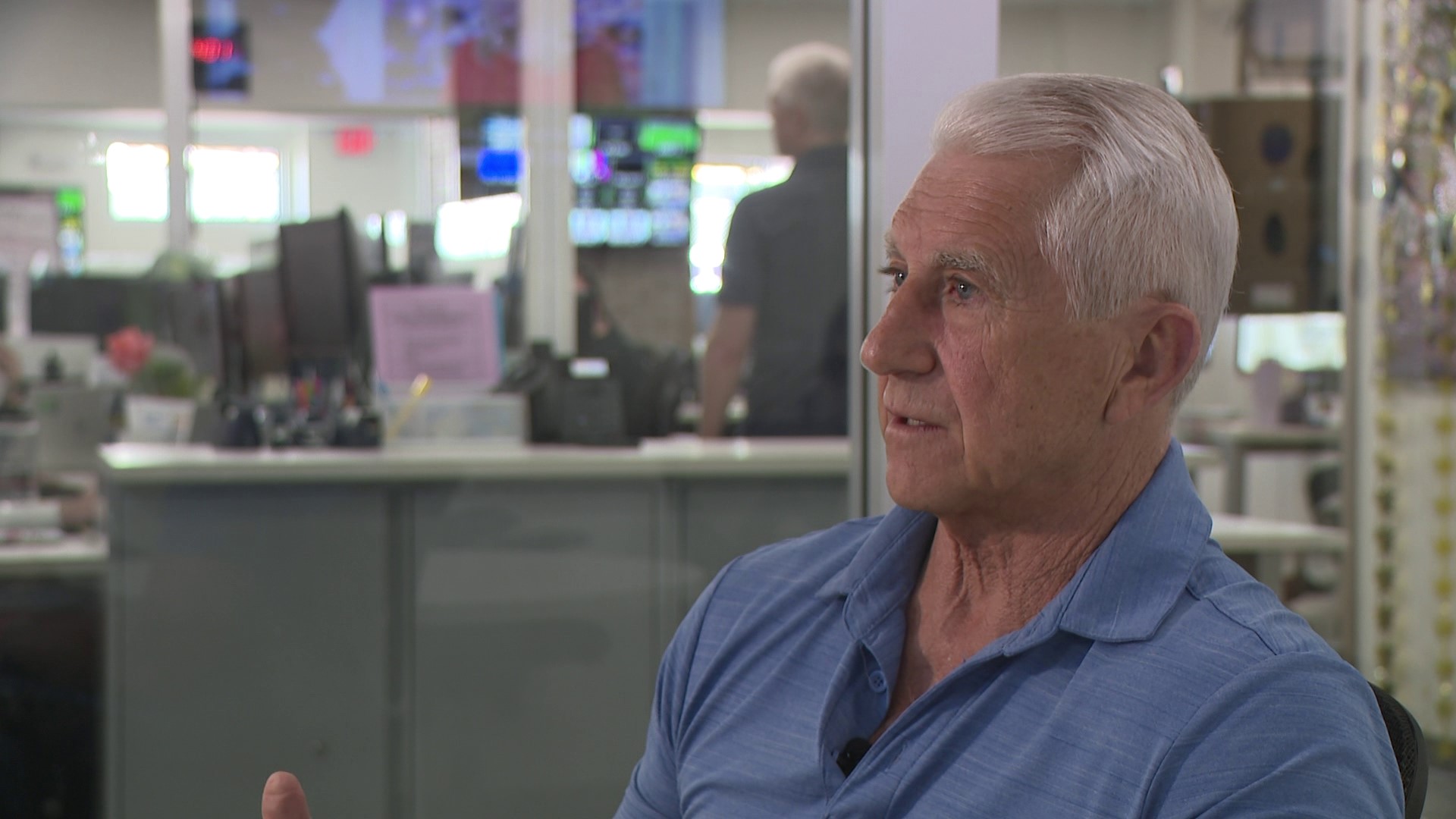

KREM 2 spoke to Michael J. Ritter, an assistant professor of political science at WSU and author of an upcoming book, "Accessible Elections," about voting by mail and the questions and concerns our viewers have about it.

Is voting by mail safe?

Voting by mail is a generally safe way to vote. Regulations exist to prevent voter fraud and to maximize the likelihood that one’s mail ballot will be accurately processed.

For example, if an individual’s ballot is found to be improperly marked – such as with a non-matching signature – Washington and a number of other states have laws mandating that the individual is contacted and given the opportunity to correct or confirm their ballot so it can be counted.

Also, given the health concerns during a pandemic, mail-in voting is likely even safer than forms of in-person voting that potentially expose one to close contact with others.

Do you think mail-in voting increases voter participation?

Mail-in voting is an attractive alternative way of voting compared to in-person Election Day voting because not only does it offer the ability for one to receive and return a ballot from the convenience of their own home, but it also expands the time individuals can vote beyond one day.

Mail-in voting is also nice when individuals are voting for down-ballot races (like state judges, county commissioners, city council members, and so on) and state initiatives and referenda about which individuals may not be initially highly knowledgeable. When filling out a mail ballot, individuals can educate themselves more about the candidates and policies involved in such contests. Individuals do not have this educational opportunity when casting ballots in-person.

More people vote in states where voting by mail is an option. This was true before the 2020 election, and it certainly is true today. My research, examining the impact of mail voting laws on voter turnout across the American states, shows that these laws boost one’s likelihood of voting by a few percentage points, compared to states that do not have this voting law. Statistics from the United States Elections Project show that states like Oregon – an all-mail voting state – have already reached if not exceeded their voter turnout totals from the 2016 presidential election, indicating that more people are voting by mail compared to 4 years ago. This is also a pattern in other states as well, where mail voting has become an increasingly popular way of voting during the pandemic.

How common was voting by mail before the 2020 election?

Mail balloting has been around a long time in the U.S. and has become more common over time. The earliest form of mail voting existed for the military dating to the Civil War. Currently, more than thirty states have either universal mail voting (meaning that most ballot casting is done via mail) or no-excuse absentee voting (meaning individuals can request a mail ballot without a specific excuse).

The two earliest all-mail voting state laws were adopted in Oregon in 1998 and Washington in 2011, with the states of Colorado, Hawaii, and Utah having joined them since then. All other states have excuse required absentee laws, which means an individual can get a mail ballot but must provide an excuse (such as an illness, business matter, or out-of-state student status) to be given one.

In 2016, according to the Current Population Survey, 18% of all ballots cast nationwide were cast via mail or absentee. This year the percentage will be higher.

How common is voter fraud?

Voter fraud is not common. Nineteenth and early twentieth century voter reforms such as voter registration and the Australian ballot (i.e., secret ballots) were key measures adopted to mitigate fraud and enhance the integrity of the voting system.

The Heritage Foundation keeps a database of what it claims to be “proven” cases of voter fraud from 1982 until today; the total cases in this data set across these nearly 40 years amounts to approximately 1,300.

The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University challenges the Heritage Foundation’s voter fraud findings, pointing out that this number is out of about 3 billion ballots cast over the course of this period, meaning that fraud is empirically very rare.

Furthermore, out of the 1,300 cases, only about 10 cases pertain to in-person impersonation, which indicates a concerted attempt to commit fraud. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, most other cases of alleged voter fraud are actually voter mistakes frequently attributable to the complexities of the U.S. voting system, or election administration issues.

How common is voter fraud in voting by mail?

Voter fraud by mail is also not very common, although, as MIT election administrator scholar Charles Stewart III notes, it is the form of voting that is technically most susceptible to such occurrences because mail balloting – rather than in-person forms of voting – removes the voter from the controlled environment of a polling office, where election officials can make sure ballots are legally completed and submitted.

University of California, Irvine, Law and Political Science Professor Richard Hasen also agrees that mail voting fraud is rare. He notes that when mail voting fraud occurs it tends to take the form of vote buying, intercepting ballots from mailboxes, or involving someone else other than the designated voter completing the ballot. However, as he further points out, these cases are frequently detected and prosecuted.

That being said, mail voting fraud is uncommon. Rigorous election administration procedures protect against fraud. For example, signature matching requirements prevent a person from casting a ballot on behalf of another, and unique bar codes per ballot prevent double voting.

Also, according to the rational choice theory of voting, committing voter fraud is not a reasonable individual-level decision. One variable in this theoretical framework weighs a person’s likelihood of voting based on the probability that their vote will be the decisive, winning one in an election. For election contests that typically involve thousands if not millions of votes, the likelihood that one’s vote – or an additional one fraudulently submitted – will sway the election results is infinitesimal, disincentivizing election fraud. Even if this disincentive were not enough, voting fraudulently is a state and federal felony charge paired with a hefty fine.

How hard do you think it would be to have a large scale voter fraud in an election?

I think it would be very difficult. There are numerous regulations that exist to prevent voter fraud, in addition to the psychological reasons previously noted that disincentivize individuals from committing such an action.